Dismantling caste is not easy

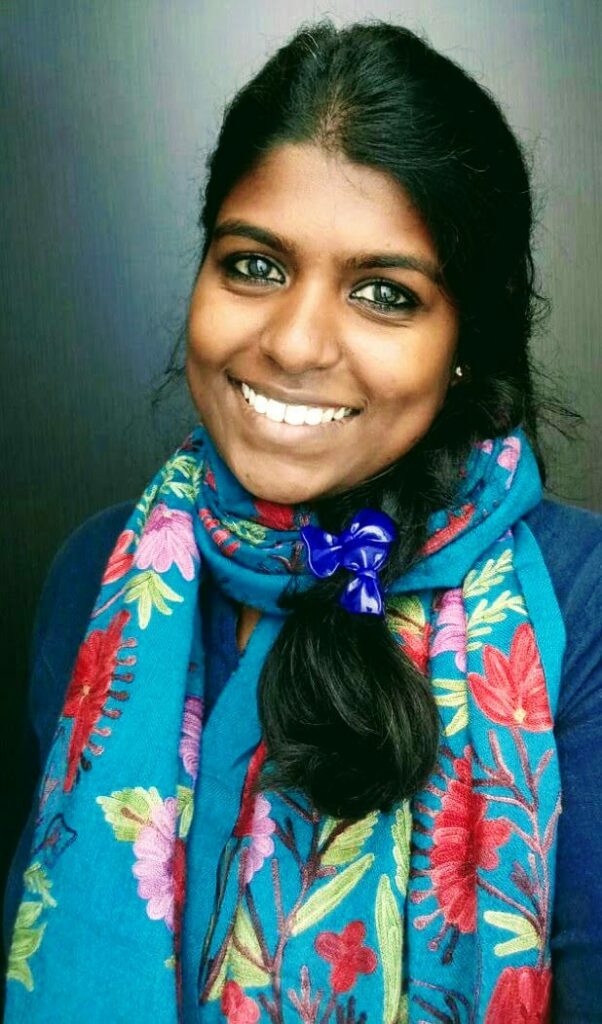

Ashwini KP, former Assistant Professor from St. Joseph’s, Bangalore, has been appointed as the sixth Special Rapporteur at the UN Human Rights Council. It becomes a benchmark as Ashwini becomes the first Asian and Indian from the Dalit community to become an independent expert on racism and other intolerance. Her journey, given the community and gender, has been overwhelming and passionate at the same time. With Abhimukham, she shares her experiences and hope for the country and the marginalised communities.

It is indeed huge to be appointed as a special rapporteur. It is even more significant to be the first Dalit woman from Asia to be nominated for the position. How do you look at this opportunity and role?

I think this opportunity comes with tremendous responsibility, considering how sensitive the whole matter of racism, xenophobia, transphobia, and religious intolerance are. Within this ambit, there are many other issues like discrimination against the Muslim diaspora, the Rohingyas, and the like. There are times when it becomes imperative to address the representation to discuss these issues, particularly for marginalised communities. For the longest time, representation has been contested by marginalised communities because it has been challenging to navigate through these spaces and represent them in a global society.

It also becomes important that I come from South Asia and a Dalit Community. As a Dalit and a woman, I also have my baggage of experiences of extreme discrimination in terms of patriarchy, caste, and many other aspects.

The concept of representation is widely spoken in all areas of society, and it can help to change the dynamics of the marginalised community by considering how our issues are addressed. In that context, I firmly believe that representation completely changes the lens through which we look at an incident.

Your position concerns identity, social environment, and contemporary politics. How do you view all of this with your lens?

Race and discrimination have been an issue since time immemorial. Society, as always, dictated the dissent and identity of an individual as to how one should be treated. Coming to my vision or perspective, I want to focus on intersectionality. When you talk about racism, it revolves around how an afro American woman, an African man, and a trans-African would be treated. How we look at things isn’t the proper approach.

We often ignore and narrate the idea of intersectionality. For example, even in mainstream feminism, women can’t be confined to one group. If you look at caste, race, and even xenophobia, the discrimination experienced by the LGBTQIA+ community, women, vary.

.Even when it comes to Muslim communities, islamophobia and discrimination within the subject come under my mandate, and I think it is something I would like to focus on.

How do you view caste in an international diaspora? How relevant do you think casteism is among Indians settled abroad?

Social identity isn’t something that can be given up very quickly, as casteism and its hierarchy benefit its followers economically, socially, and politically. Be it any institution, including race, caste, and patriarchy, they wouldn’t want it to be completely annihilated if it benefits a specific class. Regarding the Indian and South Asian diaspora, casteism has always been there. When migration took place along with other social and cultural phenomena like marriage, caste has always remained prevalent.

In the last 30-40 years, the DBA ( Dalit Bahujan Adivasi) communities have started to occupy powerful positions in IT, academics, activism, and the like; it has created a lot of ripples. People might say caste doesn’t exist and treat it as a way of socialisation; there are matrimony pages on caste relevant in the US and Europe. In fact, there are separate gurudwaras for different castes in the UK to assert the same. Even the CISCO company’s case from the US reflects on the casteism practised. We cannot turn a blind eye to caste in the Indian diaspora.

There are activist lobbies with the students who have been at the receiving end due to the discrimination, and they are also lobbying with the universities to incorporate caste as a matter of discrimination so that it becomes easier for the marginalised students to address it officially. Dalits and other progressive activists are also trying to merge anti-caste merits in the curriculum as well. Caste can only be addressed through proper affirmative actions, even in International forums.

How long do you think the journey would take for the marginalised section to be in the mainstream without having to face the discrimination?

I believe it has to be a two-way dialogue because it just cannot be the oppressed communities talking and having a conversation. It has to be the other way around, and I think one of the most significant ways to contest institutions like caste and patriarchy is to address the elephant in the room.

One major problem with caste is that privileged sections usually turn a blind eye by terming it as a thing of the past. However, people still carry the surname and privilege through the medium of marriage, endogamy etc. We also need to understand that these institutions have received religious sanctions directly or indirectly. There has been a conditioning that is why certain people and gender are looked upon in a different way, and changing it is not easy.

If you look at India, we have had one of the best progressive constitutions, and in the last 75 years, there have been a lot of changes, but dismantling caste is not easy. It is also about the mindset of the individual. Even during my conversation with progressive spaces, people address caste atrocities but point their fingers against reservation.

These are also the individuals who would back affirmative action and play the brown card in western countries. Another important aspect is to listen to the marginalised communities and their experiences to acknowledge them instead of appropriation.

Caste or the Varna system was propagated based on occupation. However, today we see that most career prospects follow their parents’ career footsteps. A doctor’s son or daughter ideally chooses the same profession. Do you see an influence of caste in such scenarios?

I think it has always been there. For example, if a family is into business and the children also wish to continue, there is capital for them to start a career in their ancestral entrepreneurship. It is, however, difficult for a marginalised community to think that way which is why there is a disproportionate representation in business when it comes to the community.

I wouldn’t be able to name even five businessmen or millionaires from the DBA communities. Therefore, I think in entrepreneurship, caste hierarchy matters a lot. But there is flexibility in education. However, caste hierarchies must have benefited a lot from the privileges to have a position of power, unlike the marginalised groups. They could even send their children to universities abroad much more quickly than someone from the DBA community.

I think with anti-caste movements, a lot of stress has been on education. One of the positive aspects of the Dalit community is the significance it has given to education. We have seen sons and daughters of manual scavengers getting into the most prestigious universities and positions. Taking the philosophies of Baba Saheb Ambedkar, particularly in the education field, has helped us navigate the contested spaces.

Tell us a little bit about Zariya? When did the thought come first to establish an organisation for the marginalised ?

The idea of having Zariya came from having the thought of allying with other communities. We wanted to focus on Dalit and oppressed Muslim communities. The idea was to bring an alliance between Dalits, Bahujan, and Adivasi women. One of the co-founders, Mariya Salim, who is also a women’s rights activist, has extensively worked on Muslim women’s issues and is also a part of Bhartiya Muslim Mahila Andolan. She has also worked on triple talaq a lot.

We were trying to have a platform where an allyship can be built among the DBA Muslim women communities. We focus on livelihood and education along with the introduction of legal aspects to women subjected to domestic violence issues and triple talaq. We were also very much inspired by Black History Month, and Dalit History Month. Likewise, we also wanted to create a Muslim history month, and we started with the idea to focus on those aspects of identity, culture, and history that have been unaddressed for the longest time.

The idea was also to reach out to people from all backgrounds and to propagate. We curated articles that a school-going child can relate to a scholar. We tried to look at the most progressive and beautiful concept of the Muslim communities. We have had articles on biryanis, Khadeeja (prophet’s wife), and writers, scholars, activists, and even homemakers from across the globe joining in. It is also a process of knowledge building by creating a sense of togetherness. We also look forward to publishing books that cater to the opinions of the DBA Muslim communities.

As a professor yourself, how has been the academic backdrop when it comes to your politics and identity?

I have had mixed experiences. If you look at a social identity as a marginalised woman, it is often dealt with intolerance. When I go to a class and teach about the constitution and talk about Baba Saheb Ambedkar, this weird hostility comes from a certain section of students. I don’t blame them, but if it is about reprimanding, we are in a generation where everything is questioned.

One cannot just get away by saying that it’s conditioning from the past. Access to information is relatively easy when compared to the 90s and early 2000s, but people tend to read less. I had handled Indian Constitution as a subject for nearly four years and had encounters where students had huge problems with the constitution.

I would then ask them if they had read the preamble, but none of them had. It is fed in by family, friends, and communities without any background checks. Even in the most progressive institutions like St. Joseph, it is challenging as a Dalit and a woman where reservation and the privilege of merit is contested. I don’t blame the students here as there are a set of teachers who also come from the progressive sections but speak the anti-reservation dialogue.

In the first year of teaching “foundation of the indian constitution,” which is even compulsory for non-humanity students, I asked students about the documentaries they would like to watch. However, they told me to screen whatever I wished, not Ambedkar’s movie. It was said straight to my face after beginning a month of teaching. This is about St. Joseph’s, regarded as one of the progressive spaces. I was definitely appalled because the audacity to say it to my face was disappointing. I also remember them denying to have read the Indian constitution even once.

There is also a difference between how male and female faculties are treated, especially if you’re young, with a lot of patriarchal, sexist tone attached. One of the college students also threatened me while talking about anti-caste movements and minority rights, which was very much part of their syllabus.

One of the other examples is about a day when I had asked students to watch ‘Pada,’ a Malayalam movie that talks about tribal land movements, and there was a Malayali student who had a problem with that.

There is also a level of intolerance among a particular set of students even to start a conversation. Indeed, a dearth of space is given to the marginalised communities to feel safe, protected, and heard. Most of the institutions’ education is confined to dress code, discipline, and attendance at the most. I think there should be a mechanism to make people fear to say something as casteist or patriarchal as the examples I mentioned. Sadly, there aren’t any for the time being. But at the same time, I have had the best of the students with progressive thoughts. It’s intolerance that is problematic.

There is indeed a rise in the anti-caste movement and politics from art to protests. How do you see it, and what is your message to all of them?

I am excited and equally proud of all the students and activists who come forward today to discuss anti-caste ideas. I have huge respect for the students and activists who come with a huge conviction and genuine concern for the issue. Many of them are even in their early teenagers, there are lawyers, brilliant artists, and illustrators, and it is a proud memento for us to see the DBA narratives in digital media.

For the longest time, our stories were neglected and excluded. If you particularly look at the elite spaces, somewhere down the line, only a few students were assertive about issues. I also had the social privilege to be assertive, which many of my fellow friends didn’t have.

When I see many youngsters being proud, vocal, and vociferous about their social identity, it is indeed a proud moment. I am also happy that intersectionality is being brought into the limelight, even student leaders coming from diverse marginalised sections.

Comments are closed.